Hinton’s entry into the field of artificial intelligence was motivated by a desire to understand the mechanisms of the human mind, a pursuit for which he found the prevailing knowledge in neuroscience and philosophy inadequate. The best shot at understanding the mind is to build one. And this is what the current LLMs do, they build a mind.

These models are viewed as a black box since their beginning. But this is starting to change with the rising field of mechanistic interpretability. The principle behind mechanistic interpretability is that networks representations can be decomposed into independent understandable features. And we can have access to those features. By reverse engineering the neural networks, we can look at neuron activations, understand the circuits of connection between them and then hopefully understand much more of what is going on. From understanding you can make progress, you can come up with new ideas, especially on the safety and alignment front. For example, we could dial up some features like helpfulness and dial down features like racism.

What are features?

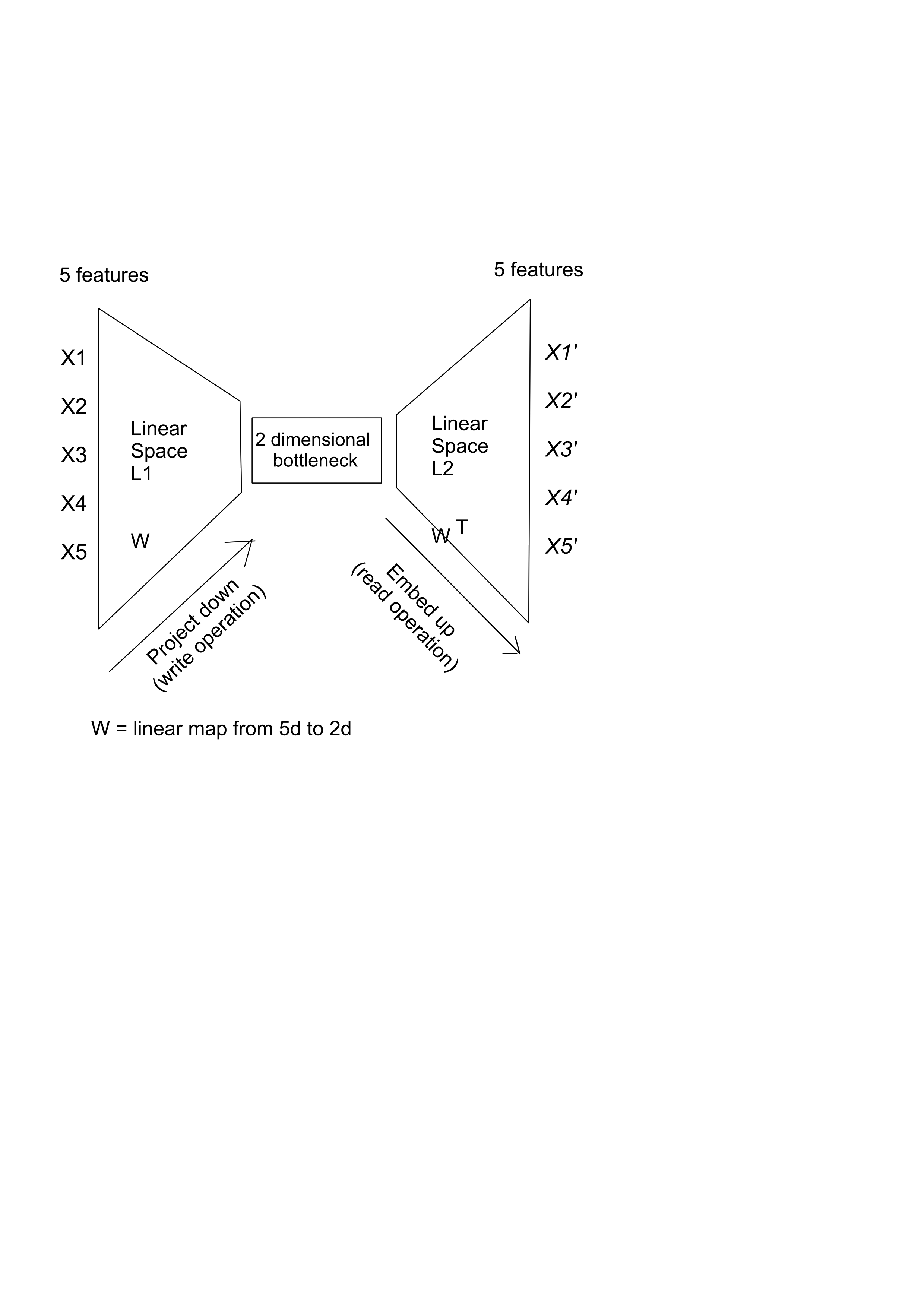

Machine learning models discover meaningful representations of data. These representations are called features. They are directions

in the multi-dimensional space in which the model embeds the data. This space is called the latent space, or the embedding space. For a model

to generalise well, this space needs to be a bottleneck, in the sense that it needs to have a (much) smaller number of dimensions

than the data on which you train.

We can see here a toy model that receives 5 input features from the training data, it embeds them in a 2d space and then it projects them back up:

This bottleneck forces compression and learning. As a side note, AI (and intelligence) can be viewed as a form of compression.

This bottleneck forces compression and learning. As a side note, AI (and intelligence) can be viewed as a form of compression.

If the model has more dimensions, than it can easily memorize the training data, without having the need to learn to generalise. The model learns to generalise when there is more training data than the models has parameters to adjust, so this limited flexibility (“degrees of freedom”) forces the model to learn only the most generalizable patterns present in the data. In conclusion, training data > degrees of freedom.

A model would want to learn as many features as possible from the data. But there is limit to the number of features it can represent. And, further more, there is a limited number of features it can represent without the features interfering with each other.

What is interference?

If features are vectors in this embedding space and we have more data than dimensions, that means that not all features can be orthogonal (perpendicular to each other).

Geometrically, orthogonality means that they are completely independent.

Two vectors u and v are considered to be orthogonal when the angle between them is 90∘. In other words, orthogonal vectors are perpendicular to each other.

The dot product between orthogonal vectors is 0 because cos 90∘ = 0:

Ideally, we would want our features to be represented by orthogonal vectors in the embedding space, because if they are orthogonal,

there is no interference between them. Activating one feature would not affect the activation of any other feature.

Interference between 2 features occurs when these features are embedded non-orthogonally in the feature space. This non-orthogonality

means that they affect each other’s predictions. Why would features be embeded non-orthogonally? Because there is a limited number of

orthogonal directions in any space, given by the number of dimensions of that space. In a 2d space, you have 2 orthogonal directions (x,y),

in a 3d space, you have 3 (x,y,z) and so on. So, we can’t have a 1-1 mapping between features and dimensions because there are so many more features

than the model has dimensions. But the model still has to represent these features somehow and it will cram multiple features into fewer dimensions at

the cost of interference between features. This is also called superposition. Intuitively, superposition is a form of lossy compression. The model is able to represent more features, but at the cost of adding noise and interference between features.

Ideally, we would want our features to be represented by orthogonal vectors in the embedding space, because if they are orthogonal,

there is no interference between them. Activating one feature would not affect the activation of any other feature.

Interference between 2 features occurs when these features are embedded non-orthogonally in the feature space. This non-orthogonality

means that they affect each other’s predictions. Why would features be embeded non-orthogonally? Because there is a limited number of

orthogonal directions in any space, given by the number of dimensions of that space. In a 2d space, you have 2 orthogonal directions (x,y),

in a 3d space, you have 3 (x,y,z) and so on. So, we can’t have a 1-1 mapping between features and dimensions because there are so many more features

than the model has dimensions. But the model still has to represent these features somehow and it will cram multiple features into fewer dimensions at

the cost of interference between features. This is also called superposition. Intuitively, superposition is a form of lossy compression. The model is able to represent more features, but at the cost of adding noise and interference between features.

Tradeoff feature benefit and feature interference

So, there is this trade off between feature benefit and feature interference. The model would want to learn the most important features first and would store them in the feature space without interference from other features. The model will ask how useful is this feature to lower the loss. More important features will be stored in orthogonal vectors, because the model would want less interference between tehn.The good news is that the large language models have a multi-dimensional embedding space that is so large that it can store many features that are nearly-orthogonal. Near-orthogonality refers to a situation where vectors are not perfectly perpendicular but are still relatively independent. So, even if you have a 10k dimensions, with near-othogonality, you can store a lot more than 10k nearly independent features. This is the advantage of highly dimensional spaces. Near-othogonality presents several benefits:

- Efficient Learning: Orthogonal features are easier to learn and optimize, as they are less likely to interfere with each other.

- Reduced Overfitting: Orthogonal representations can help to reduce overfitting by promoting a more diverse set of features.

- Less interference: Different features are represented by neurons that are independent of each other, this means that features can be combined linearly to represent a wide range of concepts without significant interferance.

Difference between superposition and polysemanticity

Neuron polysemanticity is the idea that a single neuron activation corresponds to multiple features. Conversely, a neuron is monosemantic if it corresponds to a single feature. We saw from previous research that there is a neuron in model Inception v1 responds to faces of cats and fronts of cars. This is a polysemantic neuron. Neuron superposition implies polysemanticity (since there are more features than neurons), but not the other way round because you can have less dimensions than features and polysemantic neurons.